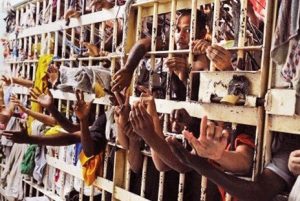

It is very unfortunate that a civilised country just like India has not codified rights of the prisoners. However, it cannot be denied that Hon’ble judiciary has not forgotten them and recognised a long list of rights of prisoners and all authorities have to follow these directions in the absence of legislation. But, practically, in absence of legislation these rights find place only on the paper with, hardly any prison’s authority following them. There are some important differences between precedent and legislation. Legislative law is clear and available to everyone, but precedent law lies with various publications at different places and there is no clarity and availability of it in one uniform book. The precedent is more powerful law than legislation and binding on all the courts in India. It is felt that, all rights of the prisoners should be codified for the awareness in the State. Moreover, prisoners are not aware of these rights, or not aware of procedure thereof. V.R. Krishna Iyer (J) has rightly observed : “In our world prisons are still laboratories of torture, warehouses in which human commodities are sadistically kept and where spectrums of inmates range from drift-wood juveniles to heroic dissenters The concept of prison discipline has undergone a drastic change in the modem administration of criminal justice system.

The trend shows a shift from the deterrent aspect to reformative and rehabilitative one. The recommendations of the Jails Committee of 1919-20 paved the way for the abolition of inhuman punishments for indiscipline. This resulted in the enforcement of the discipline in a positive manner. All India Jail Reform Committee 1980-83 has also recommended various rights of prisoners and prison discipline. Thus, a gradual trend developed in the form of enforcement of discipline motivated and encouraged by inducements like remission of punishment due to good conduct, payment of wages for labour rendered, creation of facilities like canteen and granting the privilege of writing letters and allowing interviews with friends and relatives. It must be noted that most of these “benefits” are now recognised by judiciary as part of the basic rights of the prisoners.

It is established that conviction for a crime does not reduce the person into a non-person, so he is entitled to all the rights, which are generally available to the non-prisoner. On the other hand, it cannot be denied that he is not entitled for any absolute right, which is available to a non-prisoner citizen but subject to some legal restrictions. The Supreme Court of United States as well as the Indian Supreme Court held that prisoner is a human being, a natural person and also a legal person. Being a prisoner he does not cease to be a human being, natural person or legal person. Conviction for a crime does not reduce the person into a nonperson, whose rights are subject to the whim of the prison administration and therefore, the imposition of any major punishment within the prison system is conditional upon the absence of procedural safeguards The courts which send offenders into prison, have an onerous duty to ensure that during detention, detenues have freedom from torture and follow the words of William Black that “Prisons are built with stones of Law”. So, when human rights are harassed behind the bars, constitutional justice comes forward to uphold the law.

A. Right to Fundamental Rights : The Hon’ble Supreme Court held that imprisonment does not spell farewell to fundamental rights although by a realistic re-appraisal, courts will refuse to recognize the full panoply of Part-HI enjoyed by the free citizens. Article 21 read with Article 19 (1) (d) and (5), is capable of wider application than the imperial mischief which gave it birth and must draw its meaning from the evolving standards of decency and dignity that mark the progress of the matured society. Fair procedure is the soul of Article 21. Reasonableness of the restriction is the essence of Article 19 (5) and sweeping discretion degenerating into arbitrary discrimination is anathema for Article 14. Constitutional karuna is thus injected into incarceratory strategy to produce prison justice Earlier, the Supreme Court held that conditions of detention cannot be extended to deprivation of fundamental rights. Prisoners retain all rights enjoyed by free citizens except those lost necessarily as an incident of confinement. Moreover, the rights enjoyed prisoners, under Articles 14, 19 and 21, though limited, are not static and will rise to human heights when challenging a situation arises.4 Mr. Justice Dougals reiterated his thesis when he asserted : “Every prisoner’s liberty is, of course, circumscribed by the very fact of his confinement, but his interest in the limited liberty left to him only the more substantial. Conviction o f a crime does not render one a non-person whose rights are subject to the whim of the prison administration, and therefore, the imposition of any serious punishment within the prison system requires procedural safeguards. ” Mr. Justice Marshall also expressed himself clearly and explicitly in the same terms : “I have previously stated my views that a prisoner does not shed his basic constitutional rights at the prison gate and I fully support the court’s holding that the interest of inmate.”5

- Right to human dignity, life and liberty : Art. 4 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948 proclaims: ‘No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. ‘Again Art. 10 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights proclaims that ‘all persons deprived of their liberty shall be treated with humanity and with respect for the inherent dignity or the human person.’ Securing human dignity in the criminal law administration is a matter of global concern. Invocation of criminal law is attended with arrest, imprisonment and deprivation of liberty.The Hon’ble Supreme Court has adopted annotation of Article 21 and expanded connotation of “life” given by Field J. that “life means more than mere animal existence. The inhibition against its deprivation extends to all those limbs and faculties by which life is enjoyed. The provision equally prohibits the mutilation of the body by the

amputation of an arm or leg, or the putting out of an eye or the destruction, of any other organ of the body through which the soul communicates with the other world . Right to live is not restricted to mere animal existence. It means something more than just physical survival.In new dimension of Article 21, the Hon’ble Supreme Court held that “right to live” does not mean mere confinement to physical existence but it includes within its ambit the right to live with human dignity as stated in Maneka Gandhi’s case. While expending this concept, the Hon’ble Supreme Court held that the word ‘life’ includes that it goes along with; namely the bare necessaries of the life such as adequate nutrition, clothing and shelter over the head and facilities for reading, writing expressing oneself in diverse forms, freely moving about and mixing and commingling with fellow human beings. After some time, the Supreme Court extended the concept of ‘life’ and held that ‘life’ is not limited up to death but, when a person is executed with death penalty and doctor gave death certificate and dead body was not lowered for half an hour after the certificate of death, is violating of right to life under Article 21. The Supreme Court held that right to life is one of the basic human rights, guaranteed to every person by Article 21 and not even the State has authority to violate it. A prisoner does not cease to be a human being even when lodged in jail; he continues to enjoy all his fundamental rights including the right to life. It is no more open to debate that convicts are not wholly denude of their fundamental rights. However, a prisoner’s liberty is in the very nature of things circumscribed by the very fact of his confinement. His interest in the limited liberty left to him is the more substantial.Mere arrest and captivity does not reduce a person to sub-human or non-human. Imprisonment does not ipso facto means that fundamental rights desert the detainee nor the human dignity which is dearer value of our Constitution can be bartered away. Maneka Gandhi’s case has gone a long way in humanising the criminal administration system by its innovative doctrine of procedural due process. Various aspects of human dignity have been subjected of various judicial decisions which may be discussed separately.

amputation of an arm or leg, or the putting out of an eye or the destruction, of any other organ of the body through which the soul communicates with the other world . Right to live is not restricted to mere animal existence. It means something more than just physical survival.In new dimension of Article 21, the Hon’ble Supreme Court held that “right to live” does not mean mere confinement to physical existence but it includes within its ambit the right to live with human dignity as stated in Maneka Gandhi’s case. While expending this concept, the Hon’ble Supreme Court held that the word ‘life’ includes that it goes along with; namely the bare necessaries of the life such as adequate nutrition, clothing and shelter over the head and facilities for reading, writing expressing oneself in diverse forms, freely moving about and mixing and commingling with fellow human beings. After some time, the Supreme Court extended the concept of ‘life’ and held that ‘life’ is not limited up to death but, when a person is executed with death penalty and doctor gave death certificate and dead body was not lowered for half an hour after the certificate of death, is violating of right to life under Article 21. The Supreme Court held that right to life is one of the basic human rights, guaranteed to every person by Article 21 and not even the State has authority to violate it. A prisoner does not cease to be a human being even when lodged in jail; he continues to enjoy all his fundamental rights including the right to life. It is no more open to debate that convicts are not wholly denude of their fundamental rights. However, a prisoner’s liberty is in the very nature of things circumscribed by the very fact of his confinement. His interest in the limited liberty left to him is the more substantial.Mere arrest and captivity does not reduce a person to sub-human or non-human. Imprisonment does not ipso facto means that fundamental rights desert the detainee nor the human dignity which is dearer value of our Constitution can be bartered away. Maneka Gandhi’s case has gone a long way in humanising the criminal administration system by its innovative doctrine of procedural due process. Various aspects of human dignity have been subjected of various judicial decisions which may be discussed separately.

- Right against physical violence : Custodial violence, either by police of jail staff, is not uncommon in India. A person under arrest and detention is in custo dialegis and the detainer, his custodian. Physical assault or torture is not permissible under the law and its use is violative of Art. 21 of the Constitution. Torture during the course of investigation of crimes is not justified. Custodial deaths and violence by police received strongest condemnation from the Supreme Court in a number of cases resulting in detailed instructions to the State Governments to curb such violations of human rights. Use of violence is the greatest indignity to the prisoner and it is the duty of the court to restore dignity whenever there is a complaint made to it. The right to life and personal liberty may be curtailed to a certain extent when a person is sent to imprisonment, but it is not absolutely taken away. Thus, the person imprisoned is the possessor of other fundamental rights and the residual part of Article 21 as well. The State does not give a right to take away the life or its important facets to the officers enforcing the law. If the life of an offender has been taken away, without the procedure established by the law, it would definitely amount to violation of Article 21 of the Constitution. Similarly, the life of an offender cannot be jeopardized by indulging in illegal physical torture by the jail authorities. The Supreme Court on a complaint of custodial violence to women prisoners in jail directed that those helpless victims of prison injustice should be provided legal assistance at the State’s cost and protected against torture and maltreatment. As earlier, the court held that prisoners cannot be thrown at the mercy of policemen as if it were a part of an unwritten law of crime. The Supreme Court was not happy with the attitude of prison authority and suggested that the prison authorities should change their attitudes towards prisoners and protect their human rights for the sake of humanity. The Article 5 of the UDHR, states that “no one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment”. There are words that crop up again. They mean severe beatings on the body and the soles of the feet with rubber hoses and truncheons, electronic shocks being run through the genitals and tongue, near-downing, hanging arms and legs, cigarette bums over the body, sleep deprivation or subjection to a high pitched noise and much more. These words repeated all through Amnesty’s leaflets and news settlers in the organisations mandate, in urgent action appeals and in letter members write – “cruel inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment”. Amnesty knows that two out of three people on earth live in country where torture occurs. “Torture is fundamental violation of human rights”, “…….. an offence to human dignity and prohibited under national and international law”. Amnesty described torture as “an epidemic that seemed to spread like a cancer”. In the 1970s and in the 1980s torture was reported from more than 90 countries. One point amnesty tries hard to bring home to people is that torture, is not something that only happens in third world countries. Certain regions do have a notorious history of abusing human rights but many countries carry out cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment of their citizen – even in some of the most “enlighted” countries like France, Italy and Britain where Police ill treatment is known to occur. In October 1983, Amnesty put together a twelve point plan for the prevention of torture. It told Governments, how they could take steps to prevent the torture of prisoners. For example, the highest authorities of a country can make statement telling the law enforcer that torture will not be tolerated. Amnesty called for an end to secret detention and the use of statements extracted under torture. It asked Governments to make torture illegal and to prosecute those found guilty of it. It suggested that places where prisoners are held be visited and examined regularly so that the public knows what goes on. The Hon’ble Supreme Court has observed that “right to life is one of the basic human rights. Even when lodged in jail, he continues to enjoy all his fundamental rights including the right to life guaranteed to him under Constitution. On being convicted of crime and deprived of their liberty in accordance with the procedure established by law, prisoners shall retain the residue of the constitutional rights. This right continues to be available to prisoners and those rights cannot be defeated by pleading the old and archaic defence of immunity in respect of sovereign acts which have been rejected several times by the Supreme Court”. State is liable for the death of under trial who continues to enjoy all fundamental rights including right to life. Again, it was observed by the Supreme Court that “custodial violence, torture and abuse of police powers are not peculiar to this country, but it is widespread. It has been the concern of the International Community because the problem is universal and the challenge is almost global. The courts are also required to have a change in their outlook, approach, appreciation, and attitude, particularly in cases involving custodial crimes so that as far as possible within their powers, the truth is found and the guilty should not escape so that the victim of the crime has the satisfaction that ultimately the AH majesty of law has prevailed.” The Hon’ble Supreme Court had passed an order for producing a prisoner before it. It was alleged that while the prisoner was being taken to the court he was manhandled severely by the escort police. After an enquiry, the court expressed the hope the basic pathology which makes police cruelty possible will receive Government’s serious attention and the roots of the third degree would be plucked out or otherwise Article 21, with its profound concern for life and limb, will become dysfunctional useless the agencies of the law in the police and prison establishments have sympathy for the humanist creed of that Article. Where the petition under Article 32 was filed by undertrials for enforcement of their fundamental right under Article 21 on the allegation that they were blinded by the police officer either at the time of their arrest or after their arrest, whilst in police custody, production of the report submitted by the police officer to the State Government and correspondence exchanged by police officers or noting on files made by them in enquiry order by the State Government into alleged offence.

- Right against unwarranted restraints : Use of handcuffs and iron-fetters as mechanical

device devised to prevent escape of the prisoner has sanction of law. As pointed out by Hon’ble Justice krishnaIyer there are three components of “iron’ force on the human person; firstly handcuff is to hoop harshly; second handcuff is to punish humiliatingly and to vulgarise the viewers also. And finally iron straps are insult and pain writ large, animalising the victim and the keeper. Punjab Police Rules enjoins a duty on police officers that every male person is to be escorted in police custody and whether under police arrest, remand or trial, unless he appears not to be in health or incapable of offering effective resistance by reason of age, be carefully handcuffed on arrest and before their removal from the building from which he may be taken after arrest. Even it is provided that prisoner brought into court in thereof is ‘specially’ ordered by the Presiding Officer, that is to say, handcuffs even within the Court is the rule and removal an exception. Even after the instructions issued by the Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs providing for use of handcuffs only where the accused/prisoner is violent, disorderly, obstructive or is likely to escape or commit suicide or is charged with certain serious non-bailable offences, practice of handcuffing prisoners in routine still persists. The abovesaid rules also provides for classification of accused persons for the purpose of handcuffing as ‘better class’ and ‘ordinary class’ commensurate with mode of life destiny has bestowed upon them. ‘Ordinary class’ to be handcuffed as a matter of routine. In Prem Shankar Shukla’s case the Supreme Court held this classification as unconstitutional. Secondly, the use of handcuffs as a matter of routine on prisoners of non-bailable offences punishable with three years’ imprisonment was also held as unconstitutional. Use of handcuff was held illicit only for the reasons germaine to escape or safe keeping of dangerous or desparate prisoners under circumstances so hostile to safe-keeping. Most important procedural safeguard provided in this decision on the use of handcuffs is requirement of recording of the reasons by escorting officer for applying handcuffs on the prisoner. Such reasons so recorded are required to be shown to the Presiding Officer of the court and require his approval. Once the court direct that handcuffs be removed such decision of the Court is to prevail. Except in such cases, use of handcuffs has been outlawyed.Where an accused is murder case was paraded through streets having both the hands tied with a rope and subjected to humiliation and indignity, Bombay High Court. awardedRs. 10,000 to the accused to be paid by the custodial incharge. Even after detailed instructions given by the Supreme Court where a prisoner wile being medically examined or working outside prison was handcuffed or fettered with chain, Himanchal Pradesh High Court issued instructions for compliance of such instruction by Jail authorities in the State.

Another device which drastically affect the limited freedom enjoyed by the prisoner and used as a means to prevent custodial escape, is ‘Iron fetter’.Use of such a device is lawful. Bar fetters can be used as a (1) preventive measure; and (2) punitive measure. In the first case fetters can be applied if the Supreintendent of Jail considers necessary for the safe custody of any prisoner with reference either to the ‘state of prison’ or ‘the character of the prisoner. Punjab Jail Manual which empowers the Superintendent Jail to order application of fetters is not statutory and therefore has no authority of law. However, under the Prisoner Act, the discretion of the Superintendent is circumscribed by the provisions itself. He is to be satisfied about the necessity of putting a prisoner in bar fetters keeping in view firstly the ‘state of prison’ or secondly the ‘character of the prisoner’. The reasons which prompt the Superintendent to order applicantion of fetters must be germaine to the necessity of these two considerations and a s opposed to mere ‘expediency’. The Supreme court held and laid down the following guidelines in this regard: (i) There should be absolute necessity for fetters; (ii) special reasons why no other alternative but fetters will alone secure custodial assurance, (iii) record of these reasons contemporaneously in extenso; (iv) such record should not merely be full but be documented, both, in the journal of the Superintendent and the history ticket of the prisoner. This should be in the language of prisoner so that he may have communication and recourse to redress; (v) the basic condition of dangerousness must be well-grounded and recorded; (vi) all these are conditions precedent to ‘rion’ save in a great emergency; (vi) before preventive or punitive iron (both are inflictions of bodily pains) natural justice in its minimal form shall be complied with (both audialteram and the nemojudex rules); (viii) the fetters shall be removed at the earliest opportunity, that is to say, even if some risk has to be taken it shall be removed unless compulsive consideration continue it for necessities of safety; (ix) there shall be a daily review of absolute need for the fetters, none being easily conceivable for nocturnal manacles; (x) if it is found that the fetters must continue beyond a day, it shall be held illegal unless an outside agency like the District Magistrate or Sessions Judge on materials placed, directs its continuance.Instruments of restraint, such as handcuffs, chains, irons and straitjacket, shall never be applied as a punishment. Furthermore, chains or irons shall not be used as restraints. Other instruments of restraint shall not be used except in the following circumstances : (a) As a precaution against escape during a transfer, provided that they shall be removed when the prisoner appears before a judicial or administrative authority; (b) On medical grounds by direction of the medical officer; (c) By order of the director, if other methods of control fail, in order to prevent a prisoner from injuring himself or others or from damaging property; in such instances the director shall at once consult the medical officer and report to the higher administrative authority. The patterns and manner of use of instruments of restraint shall be decided by the central prison administration. Such instruments must not be applied for any longer time than is strictly necessary. Handcuffing of undertrial prisoner is unconstitutional: The Hon’ble Justice Krishna Iyer, while delivering the majority judgement held that the provisions of Punjab Police Rules, that every undertrial who was accused on non-bailable offence punishable with more than three years jail term would be handcuffed, were violative of Articles 14, 36 Rules. 33 and 34 of “Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners” 118 19 and 21 of the Constitution of India. Hence they were held unconstitutional. The Hon’ble Supreme Court again held, where an undertrial prisoner challenged the action of Superintendent of jail putting him into bar fetters and kept him in solitary confinement was an unusual and against the spirit of Constitution and declared it a violation of right of locomotion.

- No need of handcuffing, while escorting the voluntary surrendered person : In case of Sunil Gupta the petitioners were educated social workers. They were handcuffed and taken to the court from the jail and back from court to the prison by escort party. They had voluntarily submitted themselves for arrest from “dharana”. They had no tendency to escape from the jail. In fact, they even refused to bail but chose to continue in prison for the public cause. It was held that this act of the escort party was violative of the Article 21 of the Constitution. There was reason recorded by the escort party in writing for this inhuman act. The court directed the Government to take appropriate action against the erring escort party for having unjustly and unreasonably handcuffing the petitioner.

- Undertrial prisoner cannot be kept in “leg irons” : It was held by the Supreme Court in the case of KadraPehadiya that, it was difficult to see how the four petitioners who were merely undertrial prisoners awaiting trial could be kept in leg irons contrary to all prisons regulations and in gross violation of the decision of this court in Sunil Batra’s case. The court directed the Superintendent to immediately remove leg irons from the feet of the four petitioners. The court also directed that no convict or undertrial prisoner shall be kept in leg irons except in accordance with the ratio of the decision of Sunil Batra’s case. Later on the Supreme Court declared, directed and laid down a rule that handcuffs or other fetters shall not be forced on a prisoner, convict or undertrial, lodged in a jail anywhere in the country or while transporting or in transit from one jail to another or from jail to court and back, the police and the jail authorities, on their own, shall have no authority to direct the handcuffing of any inmates of a jail in the country or while transporting from one jail to another or from jail to court and back. While intending to enforce the order, the court emphasised that if any violation of any of the direction issued by Supreme Court by any rank of the police in the country of member of the jail establishment shall be summarily punished under the Contempt of Court Act apart from other penal consequences under law.

- Right to community privilege : As already discussed, merely by imprisonment a person does not loose his fundamental rights. Imprisonment necessarily imply curtailment of freedom but within the circumstances of custodial detention, he has a right to enjoyment of life and liberty, In Kharaksingh’s case Supreme Court observed that by the term ‘life’ something more is meant than mere animal existence. The inhibition against its deprivation extends to all those limbs and faculties by which life is enjoyed. Prisoners are entitled to amenities of ordinary inmates in the prison like games, books, newspapers, reasonably good food, right to expression, artistic or other and normal clothing and bed. To eat together to sleep together or work together, to live together generally speaking cannot be denied to them except on specific grounds warranting such a course. Custodial segregation is sanctioned by law. Punitive segregation is physically harsh, destructive of morale, dehumanizing in the sense that it is needlessly degrading and dangerous to the maintenance of sanity when continues for more than a short period of time.Custodial segregation can be ordered as (i) preventive and (ii) punitive measure. As a preventive measure it can be ordered in case of infectious disease a prisoner is suffering from. If a prisoner is suffering from AIDS, it will justify is segregation from rest of the prisoners and an individual right must yield to the public interest. It can be resorted to even where a prisoner has homosexual tendencies and violent pro-clivities, as a preventive measure. Such a course can be resorted to only after compliance with procedural safeguards which will be discussed in the later part.Punitive segregation can be ordered by way of punishment for breach of jail discipline. In order to enforce discipline in jail, law declares certain acts, if committed by prisoners, as jail offences. punishable under the law. There are three kinds of custodial segregations: (1) soletary confinement; (2) separate confinement; and (3) cellular confinement. First kind of confinement is part of nature of sentence awarded to a prisoner and only court is competent to award such punishment as a part of sentence. Segregation of one person all alone in a single cell is soletary confinement. Such sentence is not in vogue now a days and is only a relic of British legacy. Separate confinement or cellular confinements can be awarded by the Superintendent as a punishment for commission of a jail offence as a measure of enforcing discipline. In separate confinement a prisoner is secluded from his fellow prisoners from communication only but is entitled to not less than one hour’s exercise per diem and to have his meals in association of one or more fellow prisoners.In Sostre Vs. Rockfeller the Supreme Court of America considered the question of due process and prison disciplinary hearing and held that written notice of charges must be given to disciplinary action defendant in order to inform him of the charges and to enable him to marshal the facts and prepare a defence apart from presence of a counsel and opportunity to cross-examine witnesses against him. Similar approach has been taken in Sunil Batra’s case by the Supreme Court. It has been held that there must be a ‘written statement by the fact finder as to the evidence and reasons for the disciplinary action.

- Right to be interview : The Supreme Court held that lawyers nominated by the District Magistrate, Session Judge, High Court and the Supreme Court will be given all facilities to interview, right to confidential communications with prisoners, subject to discipline and security considerations. Lawyers shall make periodical visits and report to the concerned court, results of their visits. Again, while showing importance of the right to free speech and expression relates to the press, the Hon’ble Supreme Court held that denial of permission to press for an interview of prisoner is a violation of press rights. In the instance case, the petitioner, a newspaper correspondent filed a petition to challenge the permission denied to interview two convicts. The court while granting the permission held that the press is entitled to interview prisoners unless weighty reasons to the contrary exist. The Supreme Court struck down the provisions, which were prohibiting the detenue to have interviews with a legal advisor of his choice and held that it was violating of the Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution, hence such provisions are unconstitutional and void. It would be quite reasonable if, a detenue has to be entitled to have interviews with his legal advisor at any reasonable hour during the day after taking appointment from the Superintendent of the Jail. Such appointment should be given by the Superintendent without avoidable delay. The Supreme Court also added that the interview need not necessarily take place in the presence of the nominated officer of department. If, the presence of such officer can be conveniently secured at the time of interview, without involving any postponement of the interview, such officer, or any other jail official may be present, if thought necessary to watch the interview but not so as to be within hearing distance of the detenue and the legal advisor.

- Right to socialize : The Hon’ble Supreme Court held that, the word personal liberty in Article 21 is of the widest amplitude and it includes the u right to socialise” with members of family and friends, subject of course, to any valid Prison Regulations which must be reasonable and non-arbitrary. The person detained or arrested has a right to meet his family members, friends and legal advisers and woman prisoners are allowed to meet their children frequently. This will keep them mentally fit and respond favourably to the treatment method. In instance case, the petitioner, a British national was detained in Tihar Jail of Delhi in connection with her alleged involvement in violation of COFEPOSA, 1974. The petitioner also raised the issue about the procedure and frequency of exercise of her right to meet her five years old daughter and her sister who was looking after the girl. The Rules of the Punjab Jail Manual, applicable in Delhi, permitted the detenus to meet friends and relatives only once a month while similar facility was available once and twice a week to the convicts and undertrials respectively. The court held the relevant provisions of the condition of the detention order to be violative of Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution. The court also found the provisions of the order prescribing that detenue can have an interview with a legal advisor only after obtaining permission of the District Magistrate and that the interview had to take place in the presence of certain officials of the Customs and Excise Department, to be invalid. The court also observed that in this regard a distinction has to be made between convicts and detenus under preventive detention, the latter being on higher pedestal compared to the former.

- Right to confidentiality of letter : The Court of Appeal of England held that prisoners’ letters to and from solicitors in contemplation of legal proceedings could not subjected to scrutiny and stoppage under the Prison Rules. The Prison authorities have limited powers to read the letters only when there are reasonable and probable grounds for believing that the same contains something in breach of security and only to the extent necessary to determine the same. The prison authority doing so is under a duty of law to maintain the confidentiality of the communication.

- Right to communication : The Hon’ble Supreme Court taking the antics of one of RJD MP inside Beur Jail as an eye opener seriously weighed the idea of disabling mobile phone services inside prison across the country to stop its misuse by Regina v Secretary of State for Home Department Ex-parte Leech, 1994 QB 198 143 criminals and influential inmates. The Supreme Court asked mobile services operators BSNL and Reliance Infocom to inform about the jamming of the mobile inside the jails. The direction comes during the hearing of a petition challenging a Patna High Court order granting bail to accused in the AjitSarkar murder case. The apex court had stayed the High Court order sending accused back to jail. Referring to the public meeting held by accused inside the Beur Jail at Patna and the mobile phones seized from him, the bench said – “there are instances when highly influential persons and the powerful personalities have misused the mobile phones while being lodged inside the prison”. It has to be stopped across India in all jails and the process could O y f begin by installing the jammers at the Central Jails.

- Right against forced labour : A convict by virtue of sentence awarded to him is required to put in labour. However, under trial prisoners cannot be put on any job nor can be forced to do labour. The practice of employing under trial prisoners on jobs out side or inside jails is illegal. Where undertrial prisoners were deputed to work outside jail wall s for fetching water and doing other duties, such practice was held in violation of prison regulations and contrary to the ILO Conventions against forced labour. Provisions in Jail Manual requiring undertrial prisoners to carry water in houses occupied by jail officials was held to be violative of Art. 21 of the Constitution and void.

- Right to amenities and facilities : Every prisoner is entitled to basic amenities and

facilities necessary for human existence. Violation of provisions of Jail Code dealing with diet, medical treatment, supply of clothing and blankets to the prisoner was held violative of legal right of prisoners warranting interference by the Court under Art. 226 of the Constitution. Prison rules in Maharashtra permitting a prisoner to send letter to his relative but not to another prisoner lodged in another jail was held to be discriminatory and arbitrary.Communication with nears and dears is right of the prisoners. Visits to prisoners by family and friends are a solace in insulation and only a dehumanize system can deprive vacarious delight in depriving prison inmates of this human amenity. Therefore, subject to prison discipline and search and other security to prison discipline and search and other security criteria the right to society of fellowman, parents and other family member cannot be denied in the light of Art. 19 and its sweep. Such a right is part of prisoner’s kit of right and shall be respected by allowing liberal interviews. Right to have interview with his lawyer is the right of prisoner and allowing only one interview in a month with members of his family is violative of his right. - Right to health and medical treatment: The Hon’ble Supreme Court in series of cases held “right to health care” as an essential ingredient under Article 21 of the Constitution. Article 21 casts an obligation on the State to preserve life. A doctor at the Government hospital positioned to meet this state obligation is, therefore, duty bound to extend medical assistance for preserving life. Every doctor whether at a Government hospital or otherwise has the professional obligation to extend his services with due expertise for protection of life. No law or State action can intervene to avoid/delay the discharge of the paramount obligation cast upon members of the medical profession. The obligation being total, absolute and paramount, law of procedure whether in statutes or otherwise which should interfere therefore with the discharge his obligation cannot be sustained and must therefore give way . Denial of the Government’s hospital to an injured person on the grounds of no availability of bed amounts to violation of ‘right to life’ under Article 21. Article 21 imposes an obligation on the State to provide medical assistance to injured person. Preservation of human life is of paramount importance. The right to medical treatment is the basic human right. The Gujarat High Court directed the jail authorities to take proper care of ailing convicts. The petitioners convicted in the Central Prison, Vadodara suffering from serious ailments were deprived of proper and immediate medical treatment for want of jail escorts required to carry them to hospital. The Gujarat High Court expressed shock and called I.G. Prison and Addl. Chief Secretary and they both acted with promptness and issued with necessary directions in this regard and held that negligent Officers were to be held personally liable. In 2005, same High Court issued directions to State Government, that all Central and District jails should be equipped with ICCU, pathology lab, expert doctors, sufficient staff including nurses and latest instruments for medical treatment in a suomo to writ. Delhi High Court held that where the Unit has obtained an interim order directing the Union of India to continue providing anti-retroviral treatment to the petitioner who was provided the same in Tihar jail and has since been released on bail.

- Right to speedy trial: The Supreme Court held that right to speedy trial is a part of the fundamental right envisaged under Article 21 of the Constitution. Delay in disposal of cases is denial of justice, so the court is expected to adopt necessary steps for expeditious trial and quick disposal of cases. The Hon’ble Supreme Court has laid down detailed guidelines for speedy trial of an accused in a criminal case but it declined to fix any time limit for trial of offences. The burden lies on the prosecution to justify and explain the delay. The court held that the right to speedy trial flowing from Article 21, is available to accused at all the stages, namely, the stage of investigation inquiry, trial, appeal, revision and re-trial. The court further said that the accused cannot be denied the right of speedy trial merely on the ground that he had failed to demand a speedy trial. The time limit has to be decided by balancing the attendant circumstances and relevant factors, including the nature of offence, number of accused and witness, the workload of the court, etc. The court comes to conclusion in the interest of natural justice that when the right to speedy trial of an accused has been infringed the charges of the conviction shall be quashed. In case of Rajdev Sharma, the accused was not found responsible for the delay in disposal of the criminal case and proceeding having endlessly delayed. After 13 years not a single witness had been examined after framing the charges. In such circumstances attitude of the investigating agency was absolutely callous. The court held that prolonged trial because of the fault of prosecution is a sufficient ground to set aside the trial. Justice Hasan through Patna High Court in a minority judgement, expressed the opinion that a day may come sooner or later when the period of less than ten years also will be treated as unjustified delay and it will be brought down to two years and it will be only then that the interest of justice will be served. He also hoped that courts everywhere and at all levels will be conscious of the right of the indicted person to get speedy disposal of his indictment and consequently the hardship that delay beyond the control of the accused causes.

- Right to bail during the pendency of appeal : The Hon’ble Supreme Court held that ‘”’refusal to grant bail” in a murder case without reasonable ground would amount to deprivation of personal liberty under Article 21. In this case six appellants were convicted by the Session Judge in a murder case and High Court in appeal also convicted the appellants and sentenced them to life imprisonment. The appellants suffered sentence of 20 months. These appellants were male members of their family and all of them were in jail. As such their defence was likely to be jeopardized. In the instance case, any conduct on their part suggestive of disturbing the peace of the locality, threatening anyone in the village or otherwise thwarting the life of the community or the course of justice, had not been shown on the part of these appellants, while they were on bail for a long period of five years during the pendency of appeal before High Court. The appellants applied for bail during pendency of their appeal before the Supreme Court, while granting the bail, the court held that refusal to grant bail amounts to deprivation of personal liberty of the accused persons. Personal liberty of an accused or convict is fundamental right and can be taken away only in accordance with procedure established by law. So, deprivation of personal liberty must be founded on the most serious consideration relevant to the welfare objectives of the society specified in the Constitution. In the circumstances of the case, the court held that subject to certain safeguards, the appellants were entitled to be released on bail. All the undertrial prisoners, who have been in remand for offences other than the specific offences under the various Acts, who have been in jail for period of not less then one half of the maximum period of punishment prescribed for the offence shall be released on bail forthwith in accordance with the direction of the Supreme Court. Andhra Pradesh High Court directed that all the criminal courts including the Sessions Courts, shall try the offences where the undertrial prisoners cannot be released, on the priority basis by following the provisions of section 309 of the Code. All the undertrial prisoners have been in jails for maximum term of which they could be sentenced on conviction, shall be released on bail on furnishing a personal bond of an appropriate amount. For the purpose of above directions for release on bail, all the criminal courts on the next date fixed for extension of remand or otherwise shall soumotu on the authority of this order shall consider the bail cases and grant bail to the undertrial prisoners on furnishing personal bond for appropriate amount and/or the appropriate sureties as necessary. All the mentally challenged / mentally retarded undertrial prisoners, who have been under detention for 18 years, 15 years and 6 years, shall be dealt with in accordance with the provisions of Chapter XXV of the Code. If, the Medical Officer of the State Government certifies that the undertrial prisoner is not mentally healthy, all such undertrial prisoners who completed maximum sentence period shall be released forthwith; and all such persons of unsound mind shall forthwith be shifted to any government institute of mental health pending necessary order from the competent criminal court for release of such persons. Further, the court emphasised that the direction issued by the court in the order, shall be complied within a period of two weeks. The court also directed that all the district judges shall regularly visit the Central Jails, District Jails, and sub-jails in their jurisdiction and take appropriate action as per the provisions of the Code.

- Right to free legal aid : A substantial part of the prison population in the country

consists of undertrials and those inmates whose trials have yet to commence. Thus, access to court and legal facilities is essential for giving a free and fair trial to these inmates, which is the mandate of Article 21 of the Constitution. The Supreme Court condemns the fact that Session Judges were not appointing counsel for the poor accused in grave cases. The defence should never be refused legal aid of competent counsel. This implies that true and legal papers should be made available to defendant alongwith the service of counsel. The Supreme Court held that a free legal assistance at State cost is a fundamental right of a person accused of an offence which may involve jeopardy to his life or personal liberty. In another case it was held that the right to free legal service is clearly an essential ingredient of reasonable, just and fair procedure for a person accused of an offence and it is implicit in the guarantee of Article 21. The State Government cannot avoid its constitutional obligation to provide free legal services to a poor accused by pleading financial or administrative inability. The State is under a constitutional mandate to provide free legal aid to an accused person who is unable to secure legal services on account of indigence and whatever is necessary for this purpose has to be done by the State. Moreover, this constitutional obligation to provide free legal services to an indigent accused does not arise only when trial commences but also attaches when the accused is for the first time produced before the Magistrate. That is the stage at which an accused person needs competent legal advice and representation and no procedure can be said to be just, fair and reasonable which denies legal advice and representation to him at this stage. To fulfil the requirement of the free legal aid, the Supreme Court has extended this right and directed the Government to provide financial aid also to the affiliated law colleges as the Government is providing to the medical and engineering colleges. The duty of the Magistrate and Government were pointed out by the Supreme Court, where blind prisoners were not produced before Magistrates subsequent to their first production and they continued to remain in jail without any remand order is plainly contrary to law. The Supreme Court also directed the State of Bihar and required every other State in the country to make provision for grant of free legal services to an accused who is unable to engage a lawyer on account of reasons such as poverty, indigence or incommunicate situation. The only qualification would be that the offence charged against the accused is such that on conviction, it would result in a sentence of imprisonment and is of such a nature that the circumstances of the case and the need of the social justice require that he should be given a free legal representative. There may be cases involving offences such as economic offences or offences against law prohibiting prostitution or child abuse and the like, where social justice may require that free legal services need not be provided by the State. The Supreme Court held that the Magistrate or Session Judge, before whom the accused appears, is under an obligation to inform the accused that if he is unable to engage the services of a lawyer on account of poverty or indigence, he is entitled to obtain free legal services at the cost of the State. Necessary directions and guidelines were issued to Magistrates, Sessions Judges and the State Government in this regard. The Supreme Court while considering the prisoner’s right to have a lawyer and reasonable access to him without undue interference from the prison staff, held that the right of a detenue to consult a legal advisor of his choice for any purpose is not limited to criminal proceeding but also for securing release from preventive detention or for filing a writ petition or for prosecuting any civil or criminal proceeding. A prison regulation cannot prescribe any unreasonable and arbitrary procedure to regulate the interviews between the detenue and the legal advisor.Free legal aid is the state’s duty and not government charity: Regarding the right of free legal aid, Justice Krishna Iyer declared that “this is the State‘s duty and not Government’s charity”.

If, a prisoner is unable to exercise his constitutional and statutory right of appeal including Special Leave to Appeal for want of legal assistance, the court will grant such right to him under Article 142, read with Articles 21 and 39A of the Constitution. The power to assign counsel to the prisoner provided that he does not object to the lawyer named by the court. On the other hand, on implication of it he said that the State which sets the law in motion must pay the lawyer an amount fixed by the court. The Hon’ble Supreme Court has taken one more step forward in this regard and held that failure to provide free legal aid to an accused at the State cost, unless refused by the accused, would vitiate the trial. It is not necessary that the accused has to apply for the same. The Magistrate is under an obligation to inform the accused of this right and enquire that he wishes to be represented on the State’s cost, unless he refused to take advantage of it. - To receive copy of the judgment at free of cost: The accused is entitled to be supplied a copy of the judgment of the convicting court. The failure to provide the copy would be violative of Article 21 of the Constitution. In the case of M.H. Haskot, the petitioner sought to appeal against the order of the High Court but he did not receive a copy of the judgment for about three years from the prison authorities. The court found this to be violative of his rights under Articles 21, 22 read with Articles 3 9-A and 42 of the Constitution. The court laid down the following principles in this regard : “(1) Courts shall forthwith furnish a free transcript of the judgment when sentencing a person to a prison term. (2) In the event of any such copy being sent to the jail authorities for delivery to the prisoner by the appellate, revisional or other court, the official concerned shall with quick dispatch get it delivered to the sentenced person and obtained an acknowledgement thereof from him. (3) Where the prisoner seeks to file an appeal or revision, every facility for the exercise of that right shall be made available by the jail administration. (4) Where the prisoner is disabled from engaging a lawyer, on reasonable grounds such as indigence or incommunicado situation, the court shall, if the circumstances of the case, the gravity of the sentence, and the ends of justice so require, assign a competent counsel for the prisoner’s defence, provided the party does not object to that lawyer. (5) The State which prosecuted the person and set in motion the process which deprived him of his liberty shall pay to assigned counsel such sum as the court may equitably fix”.

- Right to education :

- Right to higher education : The Hon’ble Supreme Court directed the State Government to see within the framework of the Jail Rules, that the appellant is assigned work not of a monotonous, mechanical, intellectual or like type mixed a title manual labour…” and said that the facilities of liaison through correspondence course should be extended to inmates who are desirous of taking up advanced studies and woman prisoners should be provided training in tailoring, doll-making and embroidery. The prisoners who are well educated should be engaged in some mental-cum-manual productive work. In an interim order dated 21st February, 2005, the Gujarat High Court allowed an undertrial to appear in the board examination commencing from 14 April, 2005 and passed a mandatory interim order directing the Gujarat Higher Secondary Education Board (GSEB) to accept Gandhi’s form, even if it was late by 9 days and issue a provisional seat number. One of the accused Mitesh Gandhi (accused of murder) filed an application before the High Court pleading that he should be allowed to appear in the class XII (Commerce) examination, while he was refused bail. It was submitted in the court that nine days delay on the part of the applicant in filling up of form was because he could not get proper information in the jail about the schedule. Rejection of the form amounted to violation of inmate’s fundamental right. Undertrial prisoner Hitesh Gandhi (20 years) was given temporary bail by Hon’ble High Court to appear in HSC Exam begins on 14th March, 2005.59 Again, in 2006, he was allowed to appear at the Exam.

- Right to receive Books and Magazines inside the Jail: The Superintendent of Nagpur Central Prison had arbitrarily fixed the number of books to be allowed to each prisoner at 12. The court held that under the Bombay Conditions of Detention Order, 1951 there was no restriction on the number of books and the only ground on which a book may be disallowed is that it was, in the opinion of the Superintendent, ‘unsuitable’. The Superintendent could not fall back on any implied power to disallow the books. Of all the restraints on liberty, that no knowledge, learning and pursuit of happiness is the most irksome and least justifiable. Improvement of mind cannot be thwarted but for exceptional and just circumstances. It is well known that books of education and universal praise have been written in prison cells. The prison officials had refused to Mr. Khan certain journals and periodicals, even though the prisoner had offered to pay for them. It was refused on the ground that, they were not included in the officials list. The court held that prisoners can be refused reading materials only if the newspapers are found ‘unsuitable’ by the authorities. In the present case prison authorities had supposedly found the journals ‘unsuitable’ because they ‘preached violence’ and criticized policies of the government in respect of Kashmir. Preventing prisoners from reading papers does not in any way relate to maintenance of discipline. Further, the court said that the word ‘unsuitable’ in clause 16 gave the State arbitrary and unregulated discretion as there were no guidelines for the exercise of power. Where a prisoner was prevented from receiving “Mao literature” by authorities, he challenged the same through the petition in Kerala High Court. The Kerala High Court held that no passage from these books could be shown, if read, to endanger security of the State or prejudice public order and so the books were allowed. The court held that there was no ground to prevent Kunnikal from obtaining these books. Article 19 (i) (a) includes the freedom to acquire knowledge, to pursue books and read any types of literature subject only to certain restrictions for maintaining the security of State and pubic order.

- Right to publication : Where a scientific book was not allowed to be published by the prison authorities, the Hon’ble Supreme Court held that there was nothing in the Bombay Detention Order, 1951 prohibiting a detenue from writing or publishing a book. The court further observed that the book being a scientific work ‘Inside the Atom’ could not in any case be detrimental to public interest or safety as envisaged under the Defence of India Rules, 1962. The person detained under Preventive Detention Act was not permitted to hand over his written work to his wife for publication, is violative of Article 21 of Constitution of India. In another case, the Hon’ble Supreme Court held that to deny the permission of publication of autobiography of Auto Shanker under the fear of defamation of IAS, IPS and its officials have no authority in law to impose prior restraint on publication of defamatory matter. The public official can take action only after the publication of it is found to be false.

- Right to reasonable wages for work : For the first time in 1977, the Hon’ble Supreme Court held that the unpaid work is bonded labour and humiliating. The court expressed its displeasure on this issue. Surprisingly, even after two decades in spite of, all discussions regarding correction and rehabilitation in the country, the A.P Government has yet to frame rules for the payment of wage to the prisoners. It was held that some wages must be paid as remuneration to the prisoner; such rate should be reasonable and not trivial at any cost. The court held that when prisoners are made to work, a small amount by way of wages could be paid and should be paid so that the healing effect on their mind is fully felt. Moreover, proper utilisation of service of prisoners in some meaningful employment, whether a cultivators or as craftsmen or even in creative labour will be good from society’s angle, as it would not be the burden on the public exchequer and the tension within. In fact, the question relating to wages of prisoner was explained by Kerala High Court in 1983, which seems to have taken the lead by the division bench. It was suggested that wages given to the prisoners must be at par with the wages fixed under the Minimum Wages Act and the request to deduct the cost for providing food and clothes to the prisoners from such wages was spumed down. On the notice of court, the Government has fixed the rate of wages as 50 paise and maximum of Rs. 1.26. The court has rejected their fixation of wages for prisoner and directed the State Government to design a just and reasonable wage structure for the inmates, who are employed to do labour, and in the meanwhile to pay the prisoners at the rate of Rs.8/- per day until Government is able to decide the appropriate wages to be paid to such prisoners. In the same year, the Hon’ble Supreme Court has held that labour taken from prisoners without paying proper remuneration was “forced labour” and violative of Article 23 of the Constitution. The prisoners are entitled to payment of reasonable wages for the work taken from them and the court is under duty to enforce their claim. The Court went one step ahead and said that there are three kinds of payment – ‘fair wages’, ‘living wages’ and ‘reasonable wages’. The prisoners must be paid reasonable wages, which actually exceeded minimum wages. The Hon’ble Supreme Court held that no prisoner can be asked to do labour without wages. It is not only the legal right o f a workman to have wages for the work but it is a social imperative and an ethical compulsion. Extracting somebody’s work without giving him anything in return is only reminiscent of the period of slavery and the system of begar. Like any other workman a prisoner is also entitled to wages for his work. It is imperative that the prisoners should be paid equitable wages for the work done by them. In order to determine the quantum of equitable wages payable to prisoners the State concerned shall constitute a wage fixation body for making recommendations. The Court also directed that each State to do so as early as possible. Until the State Government takes any decision on such “In Re Prison Reforms Enhancement of Wages of Prisoners”, recommendations every prisoner must be paid wages for the work done by him at such rates or revised rates as the Government concerned fixed in the light of the observations made above. The Court also directed all the State Governments to fix the rate of such interim wages within six weeks from the date of decision and report to this court of compliance of the direction. In the same case Thomas J said that equitable wages payable to the prisoners can be worked out after deducting the expenses incurred by the Government on food, clothing and other amenities provided to the prisoners from the minimum wages fixed under Minimum Wages Act, 1948. Wadwa J in the same case, held that the prisoner is not entitled to minimum wages fixed under Minimum Wages Act, 1948, but there has to be some, rational basis on which wages are to be paid to the prisoners. More recently, MP High Court held that, if the twin objectives of rehabilitation of prisoners and compensation to victims are to be achieved, out of the earnings of the prisoners in the jail, then the income of the prisoner has to be equitable and reasonable and cannot be so meager that it can neither take care of rehabilitation of prisoner nor provide for compensation to the victim.

- OTHER RIGHTS

-

- Right to be released on due date : No doubt, it is absolute right; all the prisoners shall be released from prison on the completion of their sentence. It is the duty of the prison staff to notify the releasing date of every prisoner in the register to be maintained by Jailer. If, any formality is needed to be done for releasing purpose, should be completed before the releasing date.

- Detention undergone to be ‘set-off’ against final sentence: Section 428 of the Code, states for set-off of the period of detention of an accused as an undertrial prisoner against the term of imprisonment imposed on him on his conviction. It only provides for a ‘set-off, but does not equate an ‘undertrial detention or the detention with imprisonment on conviction’. The provision as to set-off expresses a legislative policy; this does not mean that it does away with the difference in the two kinds of detention and puts things on the same footing for all purposes. The two requisites postulated in section 428 are : (a) During the stage of investigation, enquiry or trial of a particular case, the prisoner should have been in jail at least for a certain period; and (b) He should have been sentenced to a term of imprisonment in that case. If, the above said two conditions are satisfied, then the operative part of the provision comes into play, i.e., if the awarded sentence of imprisonment is longer than the period of detention undergone by him during the stages of investigation, enquiry, or trial, the convicted person needs to undergo only the balance period of imprisonment after deducting the earlier period from the total period of imprisonment awarded. The Hon’ble Supreme Court has interpreted the above provisions in a wider sense and held that period of detention undergone is to be set-off against the sentence of imprisonment. Section 428 only provides for set-off but does not equate an undertrial detention, or detention with imprisonment on conviction. The detention under preventive detention laws is essentially a precautionary measure intended to prevent and intercept a person before he commits an infra active act, which he had done earlier and is not punitive. Therefore, it is impermissible to set-off, period of detention under COFEPOSA against sentence of imprisonment imposed on conviction under Customs Act, in terms of section 428. It is a settled legal position that detention under the preventive detention laws is not punitive but is essentially a precautionary measure intended to prevent and intercept a person before he commits an infra active act which he had done earlier.

- Delay in release from jail amounts to ‘illegal detention’: The Hon’ble Supreme Court held that a person was acquitted by the court but was not released by the jail authority for 14 years of his precious life. The Supreme Court was first shocked by the sordid and disturbing State of affairs disclosed by the writ petition for habeas corpus filed by the petitioner for the release of a person for the unlawful detention, who was already acquitted by the court more than 14 years ago. Accordingly the petitioner also asked for compensation of illegal incarceration in which the detenue had lost his precious 14 years of life behind the bars even though he was acquitted by court. The Supreme Court held the following principles in its judgement- (1) The monetary compensation for violation of fundamental rights to life and personal liberty can be determined; and (2) If infringements of fundamental rights cannot be corrected by any other methods open to judiciary, then right to compensation is opened. The Supreme Court granted interim relief amounting to Rs. 35,000 to petitioner and also right to file regular suit in the ordinary court to recover damages from the State and its erring officials for taking away his precious 14 years of independent life which could never come back. The court has directed the subordinate court to hear the case on merit basis. Please remember that this petition was a habeas corpus writ where the remedy is only to release the illegal detenue and not to punish the offender. The Supreme Court has opened the remedy in the monetary form where there is no other way to correct it on the violation of fundamental right. We must not assess that the Supreme Court has given only Rs. 35000 as compensation for the darkest 14 years of the illegal detention but as it was habeas corpus writ and Supreme Court is also bound with the law. Here the Hon’ble Supreme Court has restrained itself from crossing the constitutional provisions.

- Power of High Court to release prisoners after pardon : Any High Court may, in any case in which it has recommended to Government the granting of a free pardon to any prisoner, permit him to be at liberty on his own recognizance.

- Right to food and water : Every prisoner shall be provided by the administration at the usual hours with food of nutritional value adequate for health and strength, of wholesome quality and well prepared and served. And drinking water shall be available to every prisoner whenever he needs it.

- Right to have adequate accommodation : The Hon’ble Supreme Court has issued direction

to the State of UP, that wherever such detentions are stored to the persons detained must be housed in a lock-up which will provide at least 40 sq. ft. per person with minimal facilities of some furniture such as a cot for each of the detained 84 Times of India, 05-01-2005 85 Rule-20 of “Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, 1957” adopted by UN and India is a party. 144 persons and supply of potable water. Having regard to the climate conditions of the place, the lock-up should provide for an electric fan. There must be hygienic arrangements for toilet. The State shall ensure the satisfaction of or these conditions wherever such arrests and detentions are resorted to. A convict lodged in jail must have reasonable accommodation to live a healthy life and enjoy his person liberty to the extent permitted by law. A reading of Rule 22, 29 and 30 of Madhya Pradesh Prison Rules shows that every sleeping ward must have certain amount of superficial area, cubic space and lateral ventilation must be allowed for each prison. If the prisoners cannot be provided with the space of 41.80 Square meters per prisoner as mandated by rules, then State Government will have to continue with the construction and expansion of jails to discharge its obligation under Article 21 of the Constitution and under the Prisons Act and the Rules towards the prisoners lodged in the jails. - Right to co-habitation with spouse : In 2000, New Zealand’s Corrections Minister Matt Robson has tried to change prison policy by introducing sex for inmates and raising children in prison. However, idea was rejected by voting to 92:8 and highly criticized by all the law experts and jurimetrics. The critics says that “more seriously, both restorative justice and attempts at rehabilitation will only be supported, and successful, if victims and the community, feel the state is still committed IJQ to ensuring that victims do not suffer more than prisoners. In December 2000, an application was moved by the wife of the prisoner, in which she claimed that, she is having natural right to have child and she cannot avail this natural right till her husband is inside the prison being a Hindu wife (faithful). One of the court from Haryana held that, we are agreed that she is having right to have child and it is not possible without the release of prisoner. According to medical science normally a woman can conceive up to the age of 45 years in India and at the time of application the age of the woman was around 27 years and her husband was to be in imprisonment for seven years more from the date. It means, at the time of his release, she will be around 34 years old. In such circumstances she can avail the right to have child for 11 years of her life. Again, the POTA Court, Ahmedabad on 13th Sep, 2004, turned down the plea of bail of a prisoner on the ground of having sex with his wife. The accused had sought 30 days temporary bail on the unique ground that abstention from sex, because of the long period in jail, was causing him and his wife immense mental trauma. The POTA court has directed the jail authorities to extend the meeting time of the accused with his wife as per the Jail Manual once in three months. The court observed, “Apex Court while defining the right to life has not incorporated conjugal right as inevitable and shrinkage of certain rights is also categorically mentioned. Therefore, this court cannot permit temporary bail for the reasons mentioned in the petition”. The court has also observed that there is no authoritative 90 pronouncement on the issue.

- Right to be released on due date : No doubt, it is absolute right; all the prisoners shall be released from prison on the completion of their sentence. It is the duty of the prison staff to notify the releasing date of every prisoner in the register to be maintained by Jailer. If, any formality is needed to be done for releasing purpose, should be completed before the releasing date.

- Right to compensation in case of miscarriage of justice :

- Right to compensation in case of custodial violence : Considering the importance of the issue raised by DK Basu through a letter and being concerned by frequent complaints regarding custodial violence and deaths in police lock-up, the Supreme Court has treated this letter as a writ petition and a notice was issued on 9th February, 1987 to the State regarding the issue. The Supreme Court held the principles that – (i) Article 21 of the constitution could not be denied to convicts, undertrial, detenues and other prisoners in custody, except according to the procedure 90 Times of India, Ahmedabad Ed 14th Sep, 2004 147 established by law. (ii) Any form of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment falls within ambit of Article 21, whether it occurs during investigation or otherwise. “Monetary or pecuniary remedy is an appropriate and indeed effective and sometimes the only suitable remedy for redressal for established infringement of the fundamental right to life of citizen by the public servants and the State vicariously liable for their act. The claim of citizen is based on the principle of strict liability to which the defence of sovereign immunity is not available and the citizen must receive the amount of compensation from the State, which shall the right to be indemnified by the wrongdoer”.

- Right to compensation in case of custodial death : The Hon’ble Supreme Court has observed that due to the gross negligence on the part of jail authorities, ‘R’ an undertrial prisoner, was subjected to serious injuries inside the jail which ultimately caused his death. It has been stated by the petitioner ‘M’, the mother of the said deceased that ‘R’ was the only bread earner in the family and on that day she had become a helpless widow with three sons to be maintained. The Supreme Court has held that it was the bounded duty of the jail authorities to protect the life of an undertrial prisoner lodged in the jail and as in the instant case such authorities have failed to ensure safety and security to “R”. The State is directed to pay a sum of Rs. 2,50,000 to the petitioner within a period of six weeks.

- Right to compensation in case of ‘illegal detention’ : When a person by a final decision has been convicted of a criminal offence and when subsequently his conviction has been reversed or he has been pardoned on the ground that new or newly discovered fact shows conclusively that there has been a miscarriage of justice, the person who has suffered punishment as a result of such conviction shall be compensated according to law, unless it is proved that the non-disclosure of the unknown fact in time is wholly or partly attributable to him. The Hon’ble Supreme Court has been very particular in safeguarding the plight of the prisoners. While enhancing the amount of compensation from Rs. 1000, awarded by the High Court to Rs. 30,000 for a delinquent subjected to three months illegal detention, the Supreme Court had held, “the payment of compensation in such cases is to be understood in the broader sense of providing relief by an order of making ‘monetary amends’ under the public law for the wrong done due to breach of public duty, of not protracting the fundamental rights of citizens. The compensation is in the nature of the ‘exemplary damages’ awarded against the wrong-doer for the breach of its public law duty”. No doubt Army Act is designed to achieve a high standard of discipline and therefore, action taken against defaulters should deter others. But humanitarian considerations do not deserve to be lost sight of. The words of TERENCE need to be remembered when he said that “extreme law is often extreme injustice”. The Supreme Court held that a person cannot be illegally detained in prison without any justification. If any person is detained illegally, he shall be entitled for compensation. The prisoners in India were the castaways of society and the prison authority showed a callous disregarded for human values it their behaviour with them and a total disregarded for their basic human rights. Their attitude and behaviour were an affront to the dignity of human beings. It is shocking that such a situation should prevail in any civilised country.

- Right to compensation in case of death of prisoner during w o rk : In 1998, the NHRC, ordered State Government of UP for payment of compensation of Rs. 1,00,000/- where the undertrial prisoner was assigned work and the person died during discharging the work.

- Right to apply for mercy and concessional application

- Right to mercy appeal (Pardon, suspension, e tc .): The Constitution of India empowered the President by Article 72 and the Governor of the State by Article 161 to pardon any of the offenders in a mercy appeal to pardon any of the punishment or remit that sentence into other kinds of sentence or suspend the sentence. Even though, the Constitution has not explained any of the grounds on which pardon may be given or not given, it is presumed that this Hon’ble office can used this power discretionarily, but in the interest of justice only. The periods which can be earned by way of remission are different in the different States. But, it is clear that all prisoners are entitled to get remission according to law enforceable in the State. This is the grace and not the right, which depends upon the character of the prisoners and circumstances of the case and seriousness of the grounds applied in the application.

- Right to leave and special leave (Furlough and Parole): All the prisoners have right to apply for the temporary release from the prison on the specified grounds mentioned in the local Act or Jail Manual, as the case may be. Jail administration is the State subject so there is not any Central Act or Guidelines prescribing the number of days for which a prisoner is eligible for a furlough or parole. Furlough and Parole are State subjects and Jail Manuals of different States are so old and confusing that their meanings are not at all clear. The Punjab and Haryana High Court held that, person convicted by the Court Martial is also entitled to seek parole for specific purposes, such as death or serious illness of a close relation and for treatment of serious disease. The Bombay High Court held that release of furlough is a legal and substantial right of the prisoner and denial of the same must be based on material facts indicating that the same would disturb public peace and tranquility. The court held that rejection of application is misconceived.

- Prisoners’ right to smoke : Smoking is dangerous to health. This slogan is written on every packet of cigarettes then also we so-called literate people generally smoke, while understanding its bad effects. How can we expect from the accused person not to smoke? In Tihar Prison any articles like Tobacco, Beedi, Cigarette or any other drug or narcotics are strictly prohibited. But on the other hand, it is also correct that this prohibition increases the corruption among the prison staff. The inmates in Gujarat jails are allowed to smoke in special smoking zones at special timings. According to jail officers, this was done to curb irregularities and corruption among the lower-rank officials, who have been alleged time and again of providing such articles to inmates at higher price than fixed by producers. The smoking was banned in Gujarat jails 10 years ago, to maintain prisoners’ health standard. However, some officials and prisoners managed to bend the rules. They used various means to smuggle in cigarettes, bidees and tobacco products. In fact, report states that lower officials sold these products at almost ten times more than normal price”. In Vadodara Central Jail cigarettes and beedis are supplied through the canteen and it has set-up a special zone for smoking.

-

- Special rights to women prisoners :